The 40-year class reunion of the Archbishop O’Hara High School intimidated me. The decades have been good to me in many ways, but I felt I was somehow inferior to my classmates. I have done many things, achieved much. But I am, in the end, a mailman. All those roads with their twists and turns, and I have little to account for a life of what some call adventure.

In the hours leading up to the time I had to leave for the restaurant, I dithered about. I sat at this computer, trying to come up with a topic to write about. But my practice of anticipating inspiration with composition, nothing came. I started and deleted numerous subjects, none of which got me past the first paragraph.

I realized after several hours that I didn’t know how to tell people about my own disappointment in how things have turned out for me so far. I have not been able to stick with a job. Aside from teaching part-time, I haven’t had a job more than four years. I’ve bounced from one undertaking to another, seemingly without reason or plan. I take up something, master it, and move on without looking back. Never being fired from a job is something to stand on, I suppose. But plenty work their whole lives without getting fired. I couldn’t think of any one thing I could put up that would match what I imagined these people had to present to each other.

Besides this, I don’t really have a retirement or can care for my wife in retirement. If I stick with the Post Office, I may be able to draw a little pension, but nothing like I would have if I had started and stuck with a job, any job, for something more than a few years.

I only decided I would attend the event, for certain, about an hour and a half before time to go. Lying down a while, I contemplated what to do with my fears and anxieties. When such fears confront me, I put myself aside and walk into them squarely. I decided I would do just that.

I also thought about the best way to approach these people. I do not know them. My high school years were not good to me. I didn’t have a good time and coped in ways that were unhealthy and not conducive to becoming a mature adult. I drank, and when I wasn’t drinking, I was thinking of drinking. Much of the after-school hours of those four years are lost to me, a blur at best. I don’t think I was unkind to others. I just didn’t know how to establish and maintain good friendships.

Incipient manic-depression also plagued me, though no one—especially not me—understood that at the time. Drinking and obsessive behaviors helped me through the worst of it but made me a needy, if sometimes neglectful friend.

So, sitting in the car outside the restaurant, I decided to do what I do best—ask other people about themselves. After all, if I could keep them talking, I wouldn’t have to tell them about my wandering past.

Then, I went in. I felt like I was diving into a pool, deep and dark and cold. There were monsters there, but they weren’t the people I was coming to see. The beasts were of my own making. They were the insecurities coming at me from my childhood, things that I thought I’d overcome in the years and work of sobriety. No matter how much I believed I’d matured, the old tapes began to play. You are not good enough, they said. You will never amount to much. You are always going to be inferior.

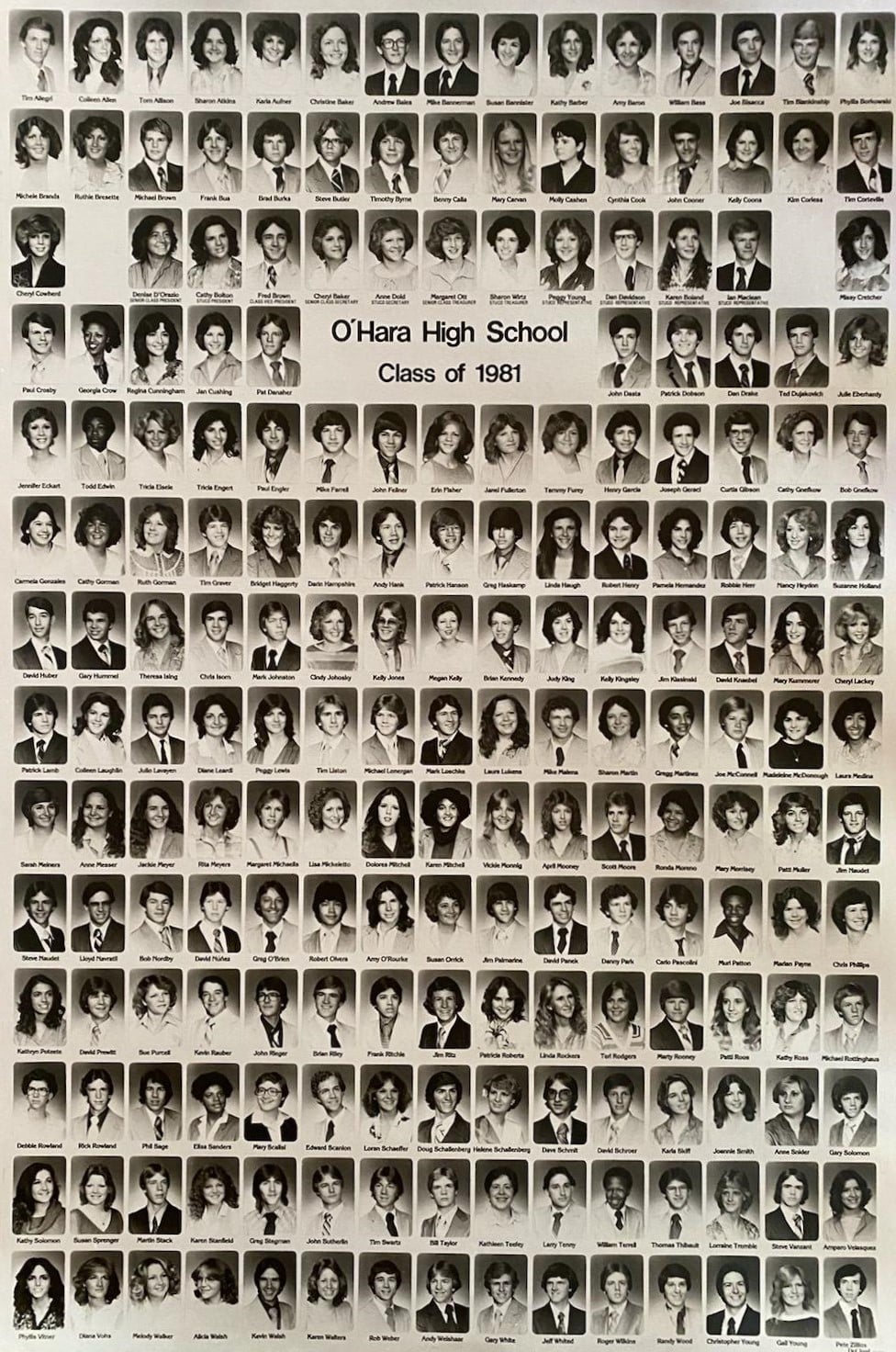

But as soon as I walked in, it was time to walk out to take the class reunion picture. Yelling and screaming to make himself heard above the din of people getting to know each other again, the photographer directed and pointed and waved. Somehow everything quieted and the crowd stilled. A couple of flashes later, the joyful noise began again. The crowd moved toward the bar. I caught one of my classmates, who I didn’t recognize, and glanced at his nametag. “What have you been up to?” I said. “How have things turned out for you?”

It was the perfect way to start a chat. I stuck with a conversation until it came to its natural end. Moving on, the questions came again and again. I learned a great deal about these people. Some have been at jobs and careers for almost the whole time since high school. A few have become successful business people, buying and selling companies, becoming executives and real estate brokers. To a person, they had done well for themselves.

Of course, there were unhappy tales of marriages gone bad, illnesses, and autoimmune diseases. A few were diabetic and others are chronically ill. But they persevere and stand as inspirations to me.

We are now old people, easing in on 60 years, not yet elderly. Our hair has grown gray, some of it has disappeared. Our glasses are thick and some of us sport trifocals now. The children have all left home. But the personalities remained. Even when we began to see past what the years had done to us, we saw again how those personal traits and perspectives have remained similar to what they were decades before.

And I was surprised at how many people kept up with me through my books and other writings. Some were seriously proud of what they saw as my accomplishments. They confronted me with my own arrogance—thinking that I somehow knew what they would think of me. I had to step back and back down. The monsters faded into the background. I wasn’t so important. We were all just doing the best with what we had.

After we had eaten dinner, mourned the dead, held drawings for high school artifacts, and socialized to the extent possible for the business hours of the establishment, I spent an hour trying to get out of there. The conversations would not cease. When finally I made it out the door, I took a moment to sit in the car in the quiet.

I learned that their experiences were not so different from mine. Many of us don’t have retirements and those that do have found themselves restless. It’s all an experiment, really, a process. We are all works in progress until termination. And that’s just all right.

You have so much more, things no one else has experienced and no one can take away.