All around us the neighborhood burned. Firecrackers, smoke bombs, fountains, and mortars. A couple of those really loud things—I don’t know what they are but I wished I had some—blew up and we felt the blast in our chests. They set car alarms honking and squealing.

A normal Fourth of July on the Westside happened while we sat quietly on the driveway. Friends had invited us to their party. They live across from the Nelson and they and their neighbors take turns blowing holes in the sky. But Virginia had to work the night before. It was best for us to have an Independence Day at home. After all, the neighborhood was like a war zone. A low, sulfurous fog covered the street and parkland under the streetlights. Aerial bursts erupted on all sides. Every now and then we could hear someone scream with delight.

And, yes, we had fireworks. They are illegal in Kansas City. Mere possession can get you a hefty ticket. But civil disobedience is the order of the day on the Fourth. Midtown, the Eastside, Downtown, Northeast, and the Westside are not places you want to be if you’re trying to have a peaceful, quiet day—or if you think the police are going to protect your quiet.

We sat in camp chairs on the driveway, Virginia, Donnie, Uncle Phil, and me. I stopped by the fireworks tent on Southwest Trafficway across the line in Kansas City, KS, where fireworks and their sale are legal. Those people selling Fourth of July supplies knew, as much as anyone, that the majority of their customers drove in from Missouri.

So, we had a couple of bags of fireworks. I was determined to stay out of the proceedings. We watched Nick blow off fireworks. Phil was the most active of us adults. He helped Nick light the punks. He supervised and even lit some of the fireworks himself.

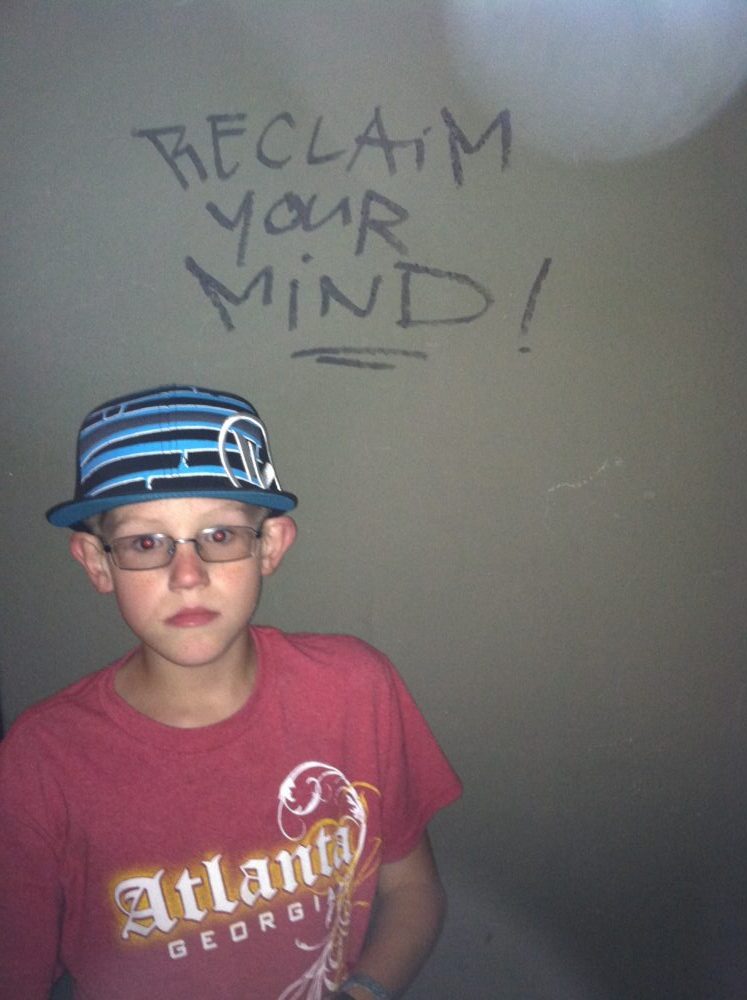

Nick is a funny animal. He’s self-contained. He can spend a lot of time alone and be just happy with that. He gets himself up in the mornings for school and get to the bus without waking us. He comes home and does his homework without being asked. In summer, he gets up late, feeds himself breakfast, and starts his day reading or watching videos on his smartphone. When he decides the time is right, he heads to the pool. He is such a trustworthy kid that he has run of the neighborhood.

Everything he does, he does with deliberation. I knew that the two, not-quite-full plastic shopping bags of goods would last us the night. There wasn’t much there. But Nick would take his time and it turns out I was right. He considered and reconsidered what he would light next. He carefully put things down on the sidewalk in the parkland across the street, fired the fuses, and then ran clear of the action. He took videos of the things he lit off. He would return after a spent pyrotechnic and review what he did and how it went. He started the thinking process again.

As I watched him, I told Donnie why I wasn’t that enthused about getting in the fireworks game. It’s not like I didn’t have the desire to blow things up. When I was a kid, Phil and I spent a good deal of time destroying things with firecrackers. We blew up anthills, packed firecrackers in mud balls and dirt clods, attached them to saplings to see if we could denude them of their fragile skins. It was a lot of fun. Firecrackers went off in our hands. We shot bottle rockets at each other. More than once, we came back home to Phil’s house or to the place we were having the celebrations charred and smoking.

Then, my dad blew up himself, my brother, and me.

He always made a big deal out of Independence Day. It was a great reason to get drunk and exercise his ego. He had the goods, too. Somewhere along the way, he and some of his gun-freak friends stole a military-grade rocket and lifted the solid propellant canister out of it. It sat in the basement, looking like a big rubber tube, next to his bullet reloading supplies and black powder cans.

Every Fourth of July, he’d carefully cut cubes off the tube, light them on one corner, and lob them across the yard. He got a big kick out it. Those little black cubes flew in like fiery red and pink meteors. For my brother, sisters, and me, he was Zeus throwing lightning bolts. He was Prometheus, the magic handler of divine fire.

Unfortunately, the drunker he became, the bolder and the riskier he got. He blew holes in the backyard with munitions that people weren’t supposed to possess, even in the 1970s. His ordinance included blank shells that he loaded into his .30-06 that he fired into the air and at the neighbors’ dogs. After a while, the black powder would come out of the basement.

One holiday, he decided he was going to create a real light show. In the early evening, he laid down a line of black powder in a big swirling shape in the grass. He used a whole can that was about six inches square. He meant to put a length of his dynamite fuse—yes, he had dynamite fuse—at one end of the line of powder so he could blow it off in the dark. But he forgot to put down the fuse. In the meantime, we shot off bottle rockets fountains, and blossoms. He did his traditional fire-throwing.

When night fell, my dad (now fully sauced), my brother, and I went out to the line of black powder. We searched around in the grass until he thought he found the end of it. Dad lit a length of dynamite fuse and laid it on the ground. My brother was standing astride the line of powder. I was a little over to one side. The powder flashed—FOOM!—before my dad could stand up.

I remember the screaming. My mother came running up to dad, who was clearly injured. My brother was yelling. My sisters were crying. My throat hurt, so I knew I had been screaming too. I was blinded by the flash and still reeling from the heat of the blast.

We stumbled out of the dark into the house. Standing in the kitchen my mother was frantic. She was panicked, running around erratically. Dad’s hand, arm, and face were black. Part of his shirt was burned away. My brother’s face was blackened. He had no eyebrows. His fire-red hair was burned away from his hairline. His legs were red.

Fortunately, there was a hospital down the street about a mile away. My dad, drunk as he was, triaged. I was shaken up and my hair was singed, but otherwise I was all right. My mom drove my brother and dad to the emergency room.

They let my brother go that night, bandaging his face, one arm, and both legs. My dad, however, was not so lucky. He suffered third-degree burns to his hand and arm. They kept him in the hospital for three days. I remember going to visit him. He lay in the hospital bed. They had an IV in his arm. The hand that held the fuse blistered such that one large bubble covered the palm of his hand and ran up his fingers. His face was raw and seeping. He still had black around the fringes of his face wound.

I felt like the whole incident was my fault. But that was my lot in life at the time. I carried the guilt of my dad’s drunken exploits, my parents’ sometimes violent fights, and just about every injury that my brother and sisters incurred.

The trauma of that event ruined fireworks for me. If no one prompts me, I do not get them for the holiday. I confess that even though I had to live through the panic and, ultimately, the guilt that I may have done something to blow my family up once, I like watching fireworks. I have a particular affinity for bottle rockets.

Since I’ve been an adult, I have bought various kinds of fireworks because the kids wanted them. I am overly cautious. The rules are: Only one firework at a time. Light the fuse and run to safety. Never shoot a firework at someone. Don’t take risks.

You would never find me messing with black powder or solid rocket propellant. I have no desire to showboat and don’t drink. I don’t hang around people who drink and blow off fireworks, ever. I don’t hang around people who like to blow things up. When I lit off fireworks with my daughter, it was always with the greatest amount of care and distance. She has had no interest in fireworks since she’s been a teenager.

Now, Nick is a different story. I buy fireworks, thinking the worst is going to happen. Something will go off in his face. We will have to go to the hospital. But I buy them for him anyway. He likes them and associates them only with good events. They are celebratory. He has a healthy fear of them. He doesn’t try to blow things up. He would never think of shooting a bottle rocket at someone.

I also like that my neighbors are pyromaniacs. Many people complain of fireworks in Kansas City. It’s against the law. Their dogs and cats hide under beds and in bathtubs. They call the cops, who never come.

As I watched Nick last night, I saw a kid who has a whole lot more on the ball than I did when I was his age. He has a sense of self-preservation. He would, I think, treat me with skepticism if I came up with a black powder scheme or tried to make what goes BOOM louder, flashier, or more destructive.

I drank a pop while I watched the neighborhood erupt. It was good enough to watch Phil and Nick and see the fireworks. They were pretty good.

And the night wound down after Nick fired off his last fountain. We cleaned up our mess and stowed the chairs. Donnie took off for home. I went back inside and petted the dogs, happy that my kid, wife, uncle, and friend were all whole.

(This post was previously published on July 5, 2016.)

Comments