The last few weeks I’ve been living the life I want to lead in retirement. Every day, I get up before everyone else to write and get the mechanism primed for the day ahead. Then, the phone takes my attention for a while before I go into the bedroom to read and fall asleep for the necessary and irreplaceable nap. After that, the day is mine for more reading, walking the dog, and thinking about the next day’s writing.

Being off work due to an on-the-job injury is not fun. The doctor put me in a sling/immobilizer for eight weeks. The bulky device did more than limit my vision of the ground in front of me. It disturbed my rest, limiting how I lie in the bed. Nights were on and off. As a stomach-sleeper, it took quite a few nights before sleep came easily. I slept in fits and starts. I snorted myself awake. My dreams became vivid and memorable—phantasms and surreal bucklings of the space-time continuum.

When I finally settled into decent rest, I was able to meet the day with open eyes and fresh smiles. My morning writing became more satisfying and complete. I’d write on my book manuscript until I had nothing more to say, sometimes up to 2,500 words. Then, I’d set my computer aside and get up from the table and let the thoughts in my head ferment for the next day.

What happened was miraculous. I started this period of work pause with 22,000 words. That represented some several months of work on days off. Even then, I always set to my work with a sense of defeat. My job really takes it out of me. Writing in the evenings, which I should have been doing every night after delivering the mail, was difficult. The 14-mile walk left my head empty as a soap bubble. I’d sit to my writing table and look at the computer screen. Nothing came. And I’m a firm believer that inspiration comes with composition and not before.

But the work injury gave me time to think. Contemplation is the key to my writing. Nothing ever comes without having first rolling around in my head, a puff of matter gathering like molecules into a substantial structure that lived in its own right. My job seems to many people to be a nice walk in the outdoors every day. But it more than that. The mail gives me no time to ruminate, the next address or package always on my mind. There’re a million details, all of which must be attended to do the job efficiently. A hitch in my attention means a skipped package that I must drive off at the end of a relay—time wasted in a job that is counted in minutes and seconds.

Free of that, my mind wandered and thoughts churned. After a few weeks, I found my manuscript progressing in ways I didn’t think possible when I was slogging along in the cold and rain. I had almost given up the thought of writing the book I’d had in my head for so long. But when the pages began to pile up, one after the other, I gained faith in my project. The stronger my confidence grew, the more pages I completed.

Then, about four and a half weeks into this period of unabridged thought and freedom, I came to end of my story—80,000 words I could feel good about. It was a good moment but one met with a sense of disappointment and depression. What would become of me now? I had fulfilled my obligation to the work. Proofreading a rewriting proved to be easier than I ever would have thought.

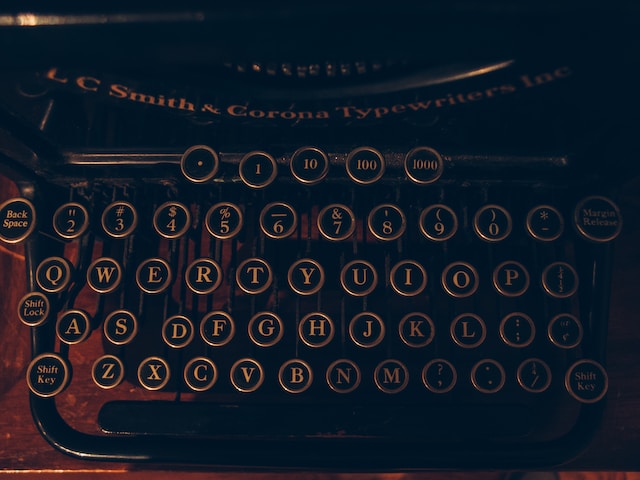

Could it be that months and years of thinking of this project allowed me to put down on paper what my manuscript was to become? Probably. As a writer, I find the typing of words on a page the culmination of hours and days of thought. The writing had already begun and I had been writing the piece for all the time I’d been thinking of it. The process still astounds me after all these years. Even this piece, the one you read now, which I sat to not knowing where it was going to go, comes easily, almost without effort. I’ve been writing this essay for weeks.

After the proofing and editing and rewriting, I gave my manuscript over to my readers. They are good people who are friends in the true sense. Their critiques will unsparing. They will not be afraid of confronting me about insipid and vapid passages. They will point out cliches. They will expose where the story deviates into unimportant tangents. They will call me on my bullshit. In short, they will point out where I have become selfish and self-absorbed, and these will be places in the manuscript that I must be more revealing or honest.

These are the best critiques. I do not need people to tell me how well I write. I have spent years getting that part of the writing process down. The manuscript needs readers who will be as cruel and discriminating as those who might one day bet their hard-earned money on what I’ve done and expect it to win.

There is more work. The manuscript is just the beginning of the life of a book. I must forge an elevator speech, synopsis, outline, and market study. Agents and publishers want something they know they can sell long before they read the work. The manuscript will not stand by itself. It needs scaffolding, fair or not, for the business end of the publishing endeavor.

But these will come, as will a good ending and title. I have faith in that. Composition is the hard part. Rewriting is the fun part. The rest is necessary and must be a part of the writer’s acuity in the written word.

So, as I come to the end of my grace period and return to work sometime in the next two weeks or so, I have an injury to thank for setting my future straight. This is how I want to spend my golden years. Writing, thinking, reading. I don’t understand those who continue to work long after they are able to retire. There is too much work for me to do. So much, in fact, that I wonder what the hell I want with a job.

Comments